Identifying and diagnosing periodontal disease

Early diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease is crucial for helping preserve dentition, decrease inflammation, and prevent further tissue and bone loss.1-3 If inadequately treated, periodontitis not only leads to tooth loss but can also compromise the general physical health of the patient.3,4

Identify patients at high risk for periodontitis

A number of factors are associated with increased risk for periodontal disease5-7:

poor nutrition

Heart disease

Some medications

Diabetes

especially if it’s uncontrolled

Smoking tobacco

which is associated with greater loss of attachment and alveolar bone

Screen for periodontal disease early and often

A combination of clinical parameters should be used to assess periodontal health in patients.

-

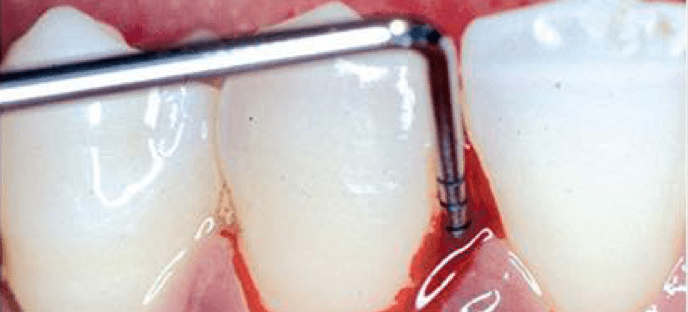

Bleeding on probing (BoP)

BoP is used to monitor health or inflammation of the gingival tissues. It may be an earlier sign of gingivitis than other signs of inflammation like redness and swelling. BoP is a good clinical indicator for disease progression or periodontal stability.2

-

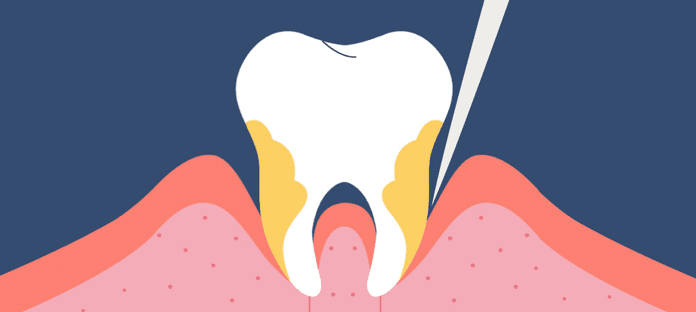

Periodontal probing depth (PPD)

PPD should be used in conjunction with BoP (but never alone) to assess oral health. Following successful treatment for periodontitis, recurrent disease can occur at individual sites, despite most of the dentition remaining well maintained and relatively healthy. This indicates that mean values of PPD, attachment levels, and bone height are not adequate predictors for sites that may become reinfected.

The most useful indicator of disease is inflammation. Historical evidence of disease may be of less relevance in the context of periodontal health on a reduced periodontium.2

-

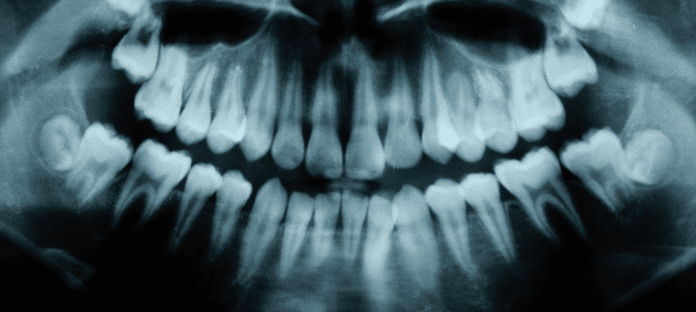

Radiologic features

Radiographs are critical for clinical assessment of the periodontium. They show historical destruction and are valuable for longitudinal determination of progressive bone loss. Once periodontitis has developed, alveolar bone loss has already occurred because of the inflammatory process. At this point, periodontal health on a reduced periodontium cannot be determined using radiographs alone.2

Did you know?

Increased tooth mobility represents a physiological adaptation to altered function rather than a sign of pathology2

It cannot be used as a sign of disease for a tooth with a reduced, but healthy, periodontium2

Talk to your patients about the link between oral and systemic health

Poor oral health can have an impact on other body systems.3,4,8 It’s important to communicate this to your patients to help them understand why treatment is important. Talk to patients about how a physical exam can uncover signs of disease, and how oral health can indicate general health status overall.9

- Be aware of medical history, especially diabetes and heart disease

- Be vigilant with pregnant women or those trying to get pregnant

- Reinforce heart-healthy goals regarding diet and exercise

- Encourage patients to quit tobacco of any kind

- Be aware of medical history, especially diabetes and heart disease

- Be vigilant with pregnant women or those trying to get pregnant

- Reinforce heart-healthy goals regarding diet and exercise

- Encourage patients to quit tobacco of any kind

Have support on hand for your patient conversations

Use the MyPerioHealth assessment tool to help guide your oral health discussions with patients in the chair.

LEARN ABOUT: The progression of periodontal disease

Stay in touch

Sign up to receive emails from Back to Basics

REFERENCES: 1. American Academy of Periodontology. Comprehensive periodontal therapy: a statement by the American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol. 2011;82(7):943-949. 2. Lang NP, Bartold PM. Periodontal health. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S9-S16. 3. Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159-S172. 4. Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. 5. Hein C. Getting it right in the long-term management of smoking-related chronic periodontitis. Contemp Oral Hyg. 2003:14-21. 6. Gum disease risk factors. American Academy of Periodontology. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.perio.org/for-patients/gum-disease-information/gum-disease-risk-factors/ 7. Gum disease and women. American Academy of Periodontology. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.perio.org/for-patients/gum-disease-information/gum-disease-and-women 8. Cullinan MP, Ford PJ, Seymour GJ. Periodontal disease and systemic health: current status. Aust Dent J. 2009;59(1 Suppl):S62-S69. 9. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. National Institutes of Health. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Published 2000. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://iiif.nlm.nih.gov/nlm%3Anlmuid-101584932X142-pgimg-1/full/2544,/0/default.jpg